JHS Bio Students Learn the Legacy of Lacks

As Black History Month wraps up and Women’s History Month kicks off, there is perhaps no better person to synchronize the two than Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman whose cancer cells have changed the world of modern medicine.

Johnston High School students in the Biology in the Environment class had the opportunity to learn more about Lacks and her immortalized human cell line, HeLa.

In 1951, Lacks was a 31-year-old mother of five, suffering from cervical cancer. When she sought treatment at John Hopkins, doctors took extra tissue for research without her consent. Her cells became

the source of the HeLa cell line, the first immortalized human cell line and one of the most important cell lines in medical research.

“This lesson has so much to it,” said JHS science teacher Janelle Woodin. “Between myself, Mrs. Horsch, and Mrs. Howe, we’ve each been able to take the lesson in a direction that supports what students have already learned and existing themes within the classroom.”

Horsch said she focused on the extensive use of the HeLa cell line to advance the knowledge of basic cell physiology. As it multiplied, it was shared more and more. In the book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, one scientist estimates that 50 million tons of HeLa cells have been grown since 1951. Lacks’ cells have gone on to:

- Test the efficacy of the polio vaccine in 1951;

- Be part of 11,000 patents;

- Serve as the foundation of research for five Nobel Prizes (since 2001).

“Knowing all of these things have been accomplished because of one woman’s cells, I asked students to put themselves in the shoes of Henrietta’s family,” Horsch said. “Her family didn’t know anything about her cell contributions until 25 years after the fact. They see all these research studies and medical accomplishments done, truly, because of their mother. Yet, no one asked for her consent to take the cells, consent to use them for research, or paid the family royalties as a result of the advancements made.”

Horsch said students approached the conversation from all angles, respectful of one another, knowing nothing could change the actions of the past.

Woodin used the lesson to explore the idea of science ethics. She said science, similar to other curriculums, can go into depth on social justice and cultural contexts.

“Bias in science is real and it makes for some really interesting discussions,” Woodin said. “We see a lot of worlds intersecting here – race, consent, medicine, science, economic status, ethics, and healthcare systems. These are big topics, but students are interested in learning more about how it happened, why it happened, what’s changed today, and what could be done differently in the future.”

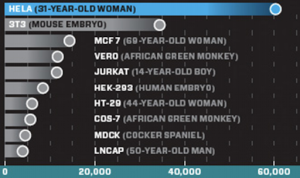

This graph from Wired Magazine in 2010 shows the number of published scientific papers based on 10 different cell lines; with HeLa being the most prevalent.

Woodin said the discussion and lesson on the HeLa Genome sets up students to tackle other questions facing the science-ethics world, such as the cultural context of climate change later in the semester.

“When we normalize conversations regarding ‘hot topic’ issues, such as healthcare and race, it helps students develop respectful dialogue with one another and acknowledge different view points,” Woodin said. “All it takes is for one student to come and tell me they learned something new or they appreciated the conversation and I know I’ve done a small part to expand their thinking.”